Why value-based care is complex, but full of potential

Moving from theory to practice – evaluating the challenges, benefits and future of value-based healthcare delivery.

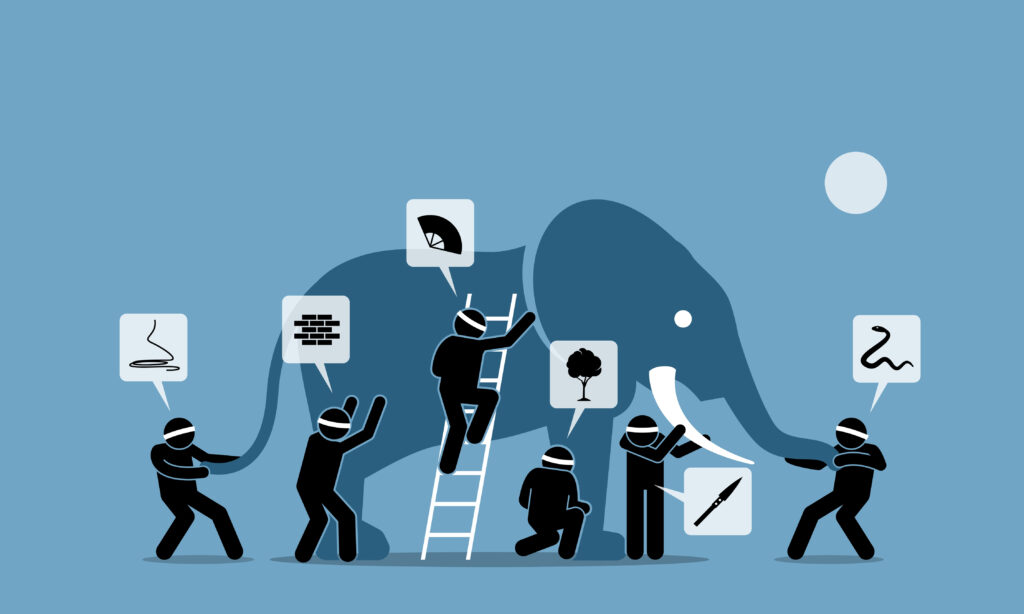

Conversations about value-based care have begun to resemble the discussions among the blind who were asked to define an elephant by touch alone. They considered its height, its breadth, thickness and function. They tried to define it and, in the end, everyone had a different opinion.

Value-based care (VBC) was a theoretical construct that emerged from the rancorous political arguments about healthcare reform. It was expressed as Value = Quality/Cost, with value being the highest priority of healthcare. There emerged a consensus that the long-standing model of fee-for services should be phased out and replaced by a value-based care model.

In the fee-for-service model, healthcare ends when the provider and the patient concur that the care produced the results desired. Over the course of treatment, each therapy session would be billed at a fixed rate. Value-based care, on the other hand, enables the provider to be paid more, based on the effectiveness of the treatment. It aligns incentives for the provider with positive outcomes for the patient, as measured by improvements in symptoms, attained more quickly in fewer sessions with fewer hospitalizations.

Value-based care has been actively promoted with such initiatives as Medicare Advantage, accountable care organizations and bundled payments. There was widespread acceptance of the model, with start-ups of all kinds emerging to implement it and giant retailers, climbing aboard to collaborate.

The fundamental reason it has been so difficult to define, characterize or judge value-based care may lie in different perceptions about the meaning of its words. Value-based care aims to lower the cost of care for a population of patients while improving outcomes. But which is the most important part of the equation – the cost of the care or the nature of the outcomes? Is value for the patient the same as value for the physician who provides the care or for the institution where the care is given, and the providers are paid?

The discussion has generated a broad range of judgments with one interested group frequently arriving at conclusions different from another’s.

Some questions about value-based care

Do patients receive better care from a system based on value than they can obtain under the fee-for-service arrangement?

Healthcare organizations may be fully committed to providing better value, but they must also focus on revenue and cutting costs. This can mean that the patient does not always have access to the specialists they want or that they may be discharged from a hospital before they feel themselves ready to go.

Do healthcare organizations have the financial and technological resources required to provide value?

Many – especially smaller practices with value-based contracts – find themselves facing daunting costs for technology. They also must add personnel to compile, analyze and report all facets of quality metrics. Practices, in contracts with multiple payers, are frustrated. According to Sterling Ransone Jr., president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, “A lot of our members, especially in small and solo practices, say they don’t have the resources to make sure they’re following the participation requirements for alternative payment models or even find out what they all are. So, they just throw up their hands and say, ‘Forget it. I’m not even going to bother.’ ”

Is fee-for service less likely to produce value for patients?

In another irony, despite the widespread optimism that greeted the introduction of value-based care, in actual practice, “Fee-for-service is still at the base of most alternative payment models,” says Tom Delbanco, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “The doctor or hospital is still billing and getting paid that way. For the front-line physician, the day-to-day incentives haven’t really changed.” And outcomes may reinforce resistance to change. For example, if immunizations are governed by fee-for-service, they are more likely to be performed. Fee-for-service thus delivers an important service that, in terms of healthcare, improves value.

Is value-based care more likely to generate value for healthcare providers?

Answers to this depend on who is asked and what they prioritize. For example, the new model requires more data collection and ongoing reporting to the payer. Fee-for-service is simpler.

Other industry stakeholders see the past decade of experimentation and implementation as a period of mixed results. Many no longer believe VBC can drive meaningful change, pointing to disappointing financial outcomes and still-frequent medical errors. And others acknowledge that value-based care is still a promising approach but one too complicated to successfully scale.

Assessments of value-base care

Ironically, one of the reasons it has been difficult to help value-based care achieve its potential is because it has become so popular.

In addition to value-based arrangements governed by Medicare and Medicaid, commercial payers are offering them. And each arrangement has its own reporting rules and its own quality metrics. Each contract must employ software and codes that are compatible – it’s yet another variant of interoperability. And it has taken a toll. The CMMI launched more than 50 models during a recent 10-year period, and only four met the requirements for continuation and expansion.

In other words, we struggle to repair and improve value-based care because not enough decision makers understand it in the same way or have the resources and experience to implement it properly – it’s too amorphous, and issues that are grave concerns for some are lower priorities for others.

The impact of COVID-19

We are all still learning lessons from the pandemic. One is that it is possible for the healthcare system to transform care delivery, and quickly.

Vaccines were formulated and brought to market with astonishing speed. Collaboration across the healthcare landscape facilitated tracking of vaccine status, and there was also a surge in virtual care. Much of this could only have occurred as swiftly as it did because of value-based care delivery models in which payment is based on outcomes, not solely on the basis of the number of services provided.

These results, in what was a remarkably short period of time, revived appreciation for value-based care. Doubts that VBC is too abstract or challenging were dispelled by the cooperative behavior of stakeholders focused on improving patient outcomes. In contrast, “Fee-for service is a volume-drive payment system; when patient volumes dropped (in the early phase of the pandemic), especially for elective and primary care, payments decreased substantially,” says Corinne Lewis, program officer of delivery system reform for The Commonwealth Fund. “Providers are recognizing the need to move toward more value-based approaches for more flexibility and protection against future volume shocks.”

Renewed acceptance of value-based care is evident. According to the Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network, more than 60 percent of healthcare payment in 2020 included some form of quality and value component, up from 53 percent in 2017 and 11 percent in 2012.

Does VBC acceptance lead to improvement?

Should VBC be retained? Apparently, yes. Must it be fixed? Some facets, yes, definitely. Some facets, not necessarily.

Here, in Health Data Land, we should home in on the technology. Investors are already betting on the continuation of value-based care. They see consolidation as companies with narrow focuses create more comprehensive end-to-end products that provide solutions to business problems rather than just software tools. There is agreement that improvements that come forward must focus on actual outcomes, not just achieving an acceptable ratio of quality to cost based on numerators and denominators.

How best to move forward

Our community must devote itself to managing the risks of value-based technology. We must fashion tools to enhance workflows and interoperability, allowing executives to monitor and manage care.

The next generation of alternative payment strategies depends on our ability to transform rich data into intelligence. We must enable the partners in healthcare to trust data, to believe our methods for deriving the data are credible and that they will yield actionable intelligence conveniently delivered and detailed enough to prescribe change.

Ultimately, we need the industry to do better than the blind tactile researchers – that is, to empower care providers to concur on standardized definitions of care, consistent utilization measurement and consistent quality measurement. Without this yardstick, there is no baseline to truly understand performance, and we will continue to be grappling with prescriptions written by the blind.

Justin Campbell is vice president of Galen Healthcare Solutions, an RLDatix company.